AB Testing: A Primer

Contents

Introduction

There are of course a million and one guides on the internet about A/B testing, but they say that teaching something is always the best way to make sure you know it.

So, without further ado, let us go over this primer on A/B testing.

A lot of the statistics and data analytics that we routinely perform on historical data allow us to look at and answer questions about correlations between variables (e.g. did sales go up over time), but it is very difficult to establish causal relationships (e.g. did sales go up over time because of our marketing efforts).

This is where A/B testing comes into play, and although it is not the only technique that can be used to establish causality, it is the gold standard in terms of definitively proving a causal relationship.

Now, as a motivating example, imagine if we own a mobile e-commerce website and we would like to know if a proposed re-design of our landing page is better for driving users further into our sales funnel, this is the perfect situation in which A/B testing can give us the answer.

So, before we dive deeper, let’s describe how A/B testing actually works at a high level.

The naive thing to do in our case would be to simply deploy the new landing page. Then, we would cross our fingers and keep our eyes on the click through rates over time. However, suppose the click through rate changed, could we attribute it to the new landing page? Or were there other confounding factors in the new period of time we were looking at that influenced user behaviour as well? We would not be able to tell.

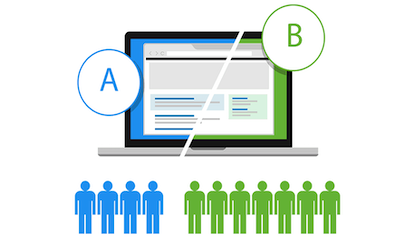

So, instead of this naive approach, what we could do is partition the traffic coming to our site and show a portion of that traffic the original landing page (the A, or control group) and the remaining portion the re-designed landing page (the B, or test group).

As you can probably intuit, this kind of experimental setup will naturally control for many of the confounding factors that may otherwise be impossible to untangle from the feature effect that we are interested in.

Defining Hypotheses

To put the above into a slightly more rigorous words, what we’re looking to do is test whether our treatment results in a statistically significant effect compared to our control.

We define our Null Hypothesis \(H_{0}\) as: the new landing page did not increase click through rates.

We perform the A/B test to see if we can disprove this hypothesis.

Estimating Sample Size Requirements

In the real world when we conduct A/B testing, most of the time you will want to expose as few users as possible to the “treatment” during the initial testing phase, and also run the test for the shortest period of time possible to get a statistically significant result. This is for a variety of reasons which are mostly practical ones (bugs, resources, giving the ability to run multiple experiments in parallel etc). Therefore, a very important step before embarking on an A/B test is to calculate the sample size requirements.

To do this, we have to define a few different concepts that go into the calculation:

-

Significance Level - Generally this is set at either 0.05 or 0.01, and is the p-value we use for significance tests. The lower significance level helps us avoid Type I errors (false positives), where the results are due to noise rather than actual differences.

-

Statistical Power - Generally this is set at 0.8, and corresponds to the probability of avoiding a Type II error (false negative), where a result was identified as negative but actually there was a difference.

-

Minimum Detectable Effect (MDE) - This parameter allows you to set the sensitivity of your experiment - in general the smaller MDE you would like to detect the larger number of samples you will need. Setting this variable generally comes from an understanding of the potential impact a feature may have (or a minimum impact for the feature to be viable for roll-out).

Now, know what the above 3 quantities are, and also knowing the historical click through rate of our landing page, we can use one of any number of online calculators (e.g. Evan’s Awesome A/B Tools to get a rough idea of the sample size we need.

However, since we’re writing this post for educational purposes, let’s also calculate it from scratch!

There are actually two different cases we need to consider:

- Sample estimation for binomial variables (proportions).

- Sample estimation for continuous variables (means).

We can get general formulas for both sample size estimation cases from (1) here and (2) here.

For proportions, this looks like:

\[n \geq \left(\frac{Z_{1-\alpha}\sqrt{p_{1}(1 - p{1})} + Z_{1-\beta}\sqrt{p_{2}(1 - p{2})}}{\mu^*}\right)^2\]For means, this looks like:

\[n \geq \left(\cfrac{Z_{\alpha} + Z_{1-\beta}}{\cfrac{\mu^*}{\sigma}}\right)^2\]The quantities are as follows:

- \(Z_{1-\alpha}\): the Z-score corresponding to our significance level \(1-\alpha\).

- \(Z_{1-\beta}\): the Z-score corresponding to $ 1-\beta $ where $ 1-\beta $$ is our statistical power.

- \(\mu^*\): the minimum detectable effect (MDE)

- \(p_{1}\): the expected click through rate of the control

- \(p_{2}\): the expected click through rate of the test

- \(\sigma\): the (pooled) standard deviation of the samples.

Note: The above equations above are for a one-tailed tests, which should be our primary mode of testing for A/B tests. For two-tailed tests, you should estimate by using the Z-score for $ 1-\frac{\alpha}{2} $.

Okay, so now we have the theory at hand, let’s code up a simple sample size estimation calculator we can use!

import scipy.stats as st

import math

def get_sample_estimate(sig, power, mde, p1, sigma1=None, var_type='binomial', tail=1):

"""

sig: stat sig level (usually 0.05 or 0.01)

power: stat power required

mde: minimum detectable effect

p1: value of control group test statistic

sigma1: value of control group test statistic std (required only for continuous var_type)

var_type: one of "binomial" or "continuous"

tail: 1 or 2

"""

# Calculate the Z_alpha given the sig and tail

if tail == 1:

z_alpha = st.norm.ppf(1 - sig)

elif tail == 2:

z_alpha = st.norm.ppf(1 - sig/2)

else:

raise Exception("tail can only be 1 or 2")

z_beta = st.norm.ppf(power)

p2 = p1 + mde

# Now we are ready to estimate the number of samples

if var_type == 'binomial':

n = ((z_alpha*math.sqrt(p1*(1-p1)) + z_beta*math.sqrt(p2*(1-p2))) / mde)**2

elif var_type == 'continuous':

n = ((z_alpha + z_beta) / (mde/sigma1))**2

else:

raise Exception("var_type can only be binomial or continuous")

return n

Interestingly, this calculation method will give us slightly different (lower) results to Evan’s Awesome A/B Tools. This is because Evan’s calculator seems to go by a slightly different formula given in this gist. I could not find the mathematical derivations of this formula so I chose not to use it.

The main thing to remember, despite the difference in absolute numbers, is that the sample size estimations are there to bring us into the right ballpark - so that we are able to scope how many % of our users we want to see the new feature and how long we need to (roughly) run our experiment for before we can get statistically significant results.

Evaluating the Results

Now, let us proceed in our hypothetical scenario (remember, we want to test a new landing page and see if it increases click through rates over the current one).

Based on our knowledge of the website and the historical data, we have defined the following parameters for our test:

p1 = 0.04(i.e. our historical click through rate is 4%)MDE = 0.01(i.e. we are hoping to see a 1 percentage point lift with the new landing page)Significance Level = 0.01(or we want to be 99% sure we don’t have a false positive result)Statistical Power = 0.8(or we want to be 80% sure we don’t have a false negative result).

Plugging these numbers into our sample size calculator yields 4087 samples required (for each group, control and test).

We decide to round up to an even 5000 for each branch as it will not be too much more effort and then proceed to partition our users on the website and run the experiment.

Here is the code we use for calling the sample sizing and then simulating the experiment:

# Calculate sample size required:

p1 = 0.04

mde = 0.01

sig = 0.01

power = 0.8

n = get_sample_estimate(sig, power, mde, p1, tail=1)

import random

def draw_samples(p, n):

"""

Draw n samples with probability p of being 1 (and 1-p of being 0)

"""

def draw_sample(p):

return 1 if random.uniform(0, 1.0) <= p else 0

o = []

for i in range(0, n):

o.append(draw_sample(p))

return o

control_group = draw_samples(0.04, 5000)

# To simulate the landing page having a 1.5% lift, we draw samples with p = 0.055 for our test group

test_group = draw_samples(0.055, 5000)

Now that we have our results from the experiment, we need to evaluate what they are and if they are statistically significant.

First, let us check the actual click through rates of our test and control groups:

ctr_ctrl = sum(control_group) / len(control_group)

ctr_test = sum(test_group) / len(test_group)

print("Control CTR: {}%".format(ctr_ctrl * 100))

print("Test CTR: {}%".format(ctr_test * 100))

# Control CTR: 4.24%

# Test CTR: 5.779999999999999%

So, with this experiment, we see that our control group has reported a CTR of ~4.24% over 5000 samples, compared to our test group which has reported a CTR of ~5.8%. This is obviously a good start, but we now need to know if this difference is statistically significant.

Generally, for testing difference in proportions, the Chi-Square test is the go-to statistical test.

We can invoke the scipy library which we imported earlier to help us easily run the Chi-Square test.

f_obs = [len(list(filter(lambda v: v == 0, test_group))), len(list(filter(lambda v: v == 1, test_group)))]

f_exp = [len(list(filter(lambda v: v == 0, control_group))), len(list(filter(lambda v: v == 1, control_group)))]

st.chisquare(f_obs, f_exp)

From this, we obtain two things:

- The Chi-Square test statistic:

29.205285225642722 - The p-value:

6.510138201463369e-08

This p-value is basically 0, which is far less than our significance level of 0.01 and which means we are more than fine to reject our null hypothesis.

As a matter of principle, we should also check the statistical power we obtain for this test, although it should not have am impact on our results.

There are two ways to do this: first, we could run simulations in order to see in what percentage of simulated experiments did our test reject the null hypothesis (given we know that the new landing page increases the CTR), or, there is also an approximation formula we can use (taken from here).

\[\lambda = n \sum_{i=0}^{1}\frac{(O_{i} - E_{i})^2}{E_{i}}\]In this case n is the number of samples.

r_int = []

for i in (0, 1):

o = len(list(filter(lambda v: v == i, test_group)))

e = len(list(filter(lambda v: v == i, control_group)))

r_int.append((o - e)**2 / e)

print("Power: ", st.chi2.cdf(sum(r_int) * 5000, 1))

We get in this case Power: 1.0, so we can say with a very high degree of certainty that our new landing page works, and it should be rolled out asap to all members!

All code is available on the following notebook on my github: here.

Till next time!

-qz