How Computers Work - Part 1

Stop and think about this for a second. Do you really know how a computer works? I mean, really really?

This is a question that has been sitting patiently on the edge of my consciousness for years, waiting for its turn to be addressed. Because, in all honesty, even though I use a computer for hours per day and have done so for pretty much every day of my adult life (and for most of my childhood too, come to think of it), I cannot in good conscience claim to be able to describe how it works in the way, for example, I could describe how a bicycle works (fun aside; describing how a bicycle works may be harder than you think.)

I thus endeavour in this blog post to address this, and take you, dear reader, on this journey of discovery with me!

Due to length, it will be a two parter. In this part, I will cover how something we see in the UI becomes translated down into binary code, and in the next part, I will cover how this binary code is actually executed.

Starting from the Basics

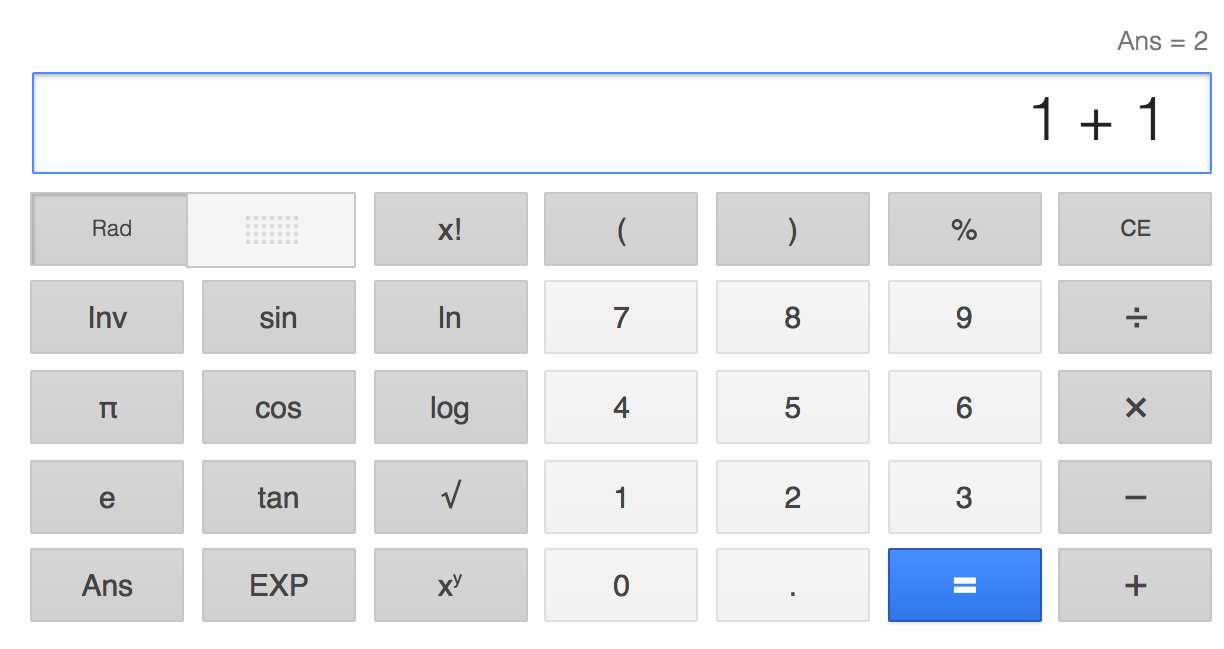

I’m not ashamed to admit it, but I have, now and again, used a calculator app for 1+1 (y’know, just to make sure. Those pesky numbers can be pesky). So, let us use that as our example. We are (I hope) all at least passingly familiar with how we might use a calculator app for 1+1.

Fig 1: How to be as insecure in your math skills as me.

Now, after we use this UI and click the calculate button, what’s going on? Well, some code runs that performs this calculation, we all know that right?

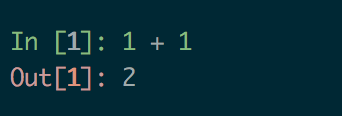

In Python, my language of choice, the code that gets run looks pretty much the same as using the calculator (except, you know, more hacker-y colours and fonts that look way cooler geekier).

Fig 2: How to be insecure in your math skills, but in a geekier way.

But how does this code work? Into the rabbit hole we go!

The Next Layer Down: Bytecode

Most modern programming languages are what we would class as high level languages. That means they have syntax that is fairly human readable. For example, in python if I wanted my program to write out the phrase “Hello World”, the code would be: print "Hello World".

Fig 3: If only 'import money' worked.

This, however, is not a language that processers can understand - we know that computers run on binary, and this doesn’t appear to be binary at all!

So, the next step is to make a translation. This is generally where the interpreter or the compiler comes into play (depending on the language). In Python, we actually have both.

First of all, the compiler takes the code we have written and translates it into something that’s closer to binary (but not binary). This is called bytecode.

For our 1+1 scenario, the bytecode looks like this:

|\x00\x00|\x01\x00\x17S

Not very human readable and not quite machine readable either… what does this mean? Well, it means the following:

0 LOAD_FAST 0 (0)

3 LOAD_FAST 1 (1)

6 BINARY_ADD

7 RETURN_VALUE

So - this seems to make sense - the instruction starting at byte 0 loads a variable (from memory position 0), the instruction starting at byte 3 loads another variable (from memory position 1). Then they are added together, and returned.

But this is pretty much the same thing as what we wrote in the high level language, and yet it isn’t executable on the machine, so…why do we even have this?

The answer lies in a design decision taken by Python for portability reasons.

There are a huge variety of different processors in use around the world today - most ubiquitous being Intel and AMD’s, but many others exist (e.g. ARM processors for the smartphone world), and of course, we have a whole bunch of different operating systems which run on top of these processors (Windows, OSX, various flavours of Linux etc). Ultimately, the operating system is responsible for managing the execution of any code that resides on the system, so, for each different operating system and hardware combination, we need a slightly different flavour of the same program.

For languages like C, which are not quite as friendly as Python, the source code must be compiled for each flavour of system that it wants to be run on. But this is where the Python interpreter comes in. The interpreter provides an abstraction layer which takes care of this final translation step without us needing to worry about it.

But, all of these details aside, we eventually end up with what is known as Machine Code.

Digging Deeper: Assembly Language & Machine Code (Binary)

Python’s interpreter will translate the bytecode into binary directly. But this binary code can be represented by assembly language.

Is assembly language binary? Nope. But it’s a direct representation of the binary code. The final layer of abstraction.

Just as programming languages like Python have a syntax, all processors also expose what is known as an instruction set (you may have heard the phrase “x86 Processor”, well the ‘x86’ here refers to the instruction set that the processor implements).

Here is some assembly language, and the binary equivalent that adds two numbers together (taken from: http://people.uncw.edu/tompkinsj/242/BasicComputer/AddTwoNumbers.htm).

ASSEMBLY BINARY HUMAN

ORG 100 /Origin of program is location 100

A, DEC 1 0000 0000 0000 0001 /Decimal operand (set A = 1)

B, DEC 1 0000 0000 0000 0001 /Decimal operand (set B = 1)

C, DEC 0 0000 0000 0000 0000 /Sum stored in location C (initialise to 0)

LDA A 0010 0001 0000 0100 /Load operand from location A

ADD B 0001 0001 0000 0101 /Add operation from location B

STA C 0011 0001 0000 0110 /Store sum in location C

HLT 0111 0000 0000 0001 /Halt computer

END

Because our program is very simple, the assembly language looks very similar to the python bytecode we saw above, which looks pretty similar to the code we wrote in python.

The instruction set of a processor is fairly small, containing only the basic necessary instructions that are needed to make computations (e.g. moving things to and from memory, basic mathematical operations and boolean logic operations, among a few other things). Think of it as the most basic lego building blocks that you get.

What determines the instructions that are to be included in a processor instruction set? Well, there are a number of factors, but a basic pre-requisite is that any instruction set has to be turing complete.

What does it mean to be turing complete?

To put it simply, to be turing complete means the processor must be able to fully simulate a turing machine. A turing machine - named after Alan Turing, was perhaps the seminal contribution to the field of computer science. It is a machine (or rather, a mathematical model), that models how things are computed. Or, another way to think about it is that anything that can possibly be computed with computers, can be done with a turing machine. Thus, if a processor’s instruction set is turing complete, then the processor can compute anything that can be computed.

Taking a Breath

Okay - so, in this blog post, we’ve pierced the veil.

We’ve gone from looking at the UI of a calculator app, to understanding how those button presses are represented by high level python code, which is then compiled into bytecode, which is then interpreted into machine code and we’ve seen for our small 1+1 example just what each stage sort of looks like.

Now though, is where I think it gets really interesting. How does it actually run? At the end of the day, a processor is just a piece of silicon arranged in a very peculiar way which we’ve hooked up to some electricity (or, as I’ve also heard it described: a processor is just a rock we’ve put lightning inside of and tricked into thinking).

So, how does it take those rather abstract 1’s and 0’s and actually do stuff with them? Why does it even need to be 1’s and 0’s? Why can’t it be 0’s 1’s and 2’s?

This, I shall tackle in the the next part!

-qz

ps. I am in these matters an amateur trying to make sense of things as best I can, that means that 1. I cannot guarantee that everything will be 100% technically correct, and 2. I welcome any comments to point out any inaccuracies!