Potatolemon - Layers and Networks

Previously on Potatolemon…

Adding Abstraction

Previously on potatolemon, we arrived at the code for one Neuron. But, of course we know that networks can be comprised of hundreds of neurons (or more)!

In order to make this a feasible library, we have to add some abstraction so we can make it easy to work with the entire network at once (especially once we get towards implementing backpropagation).

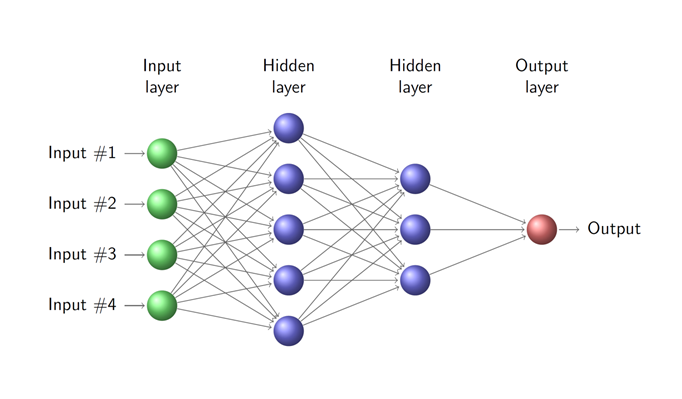

If we are building a classic densely connected Neural Network as per the figure above, then the two abstractions that make sense given we’ve built a Neuron already are an abstraction for a layer (which is a collection of neurons) and a network (which is a collection of layers).

The layer should have the ability to extract the weights of the underlying neurons (and also set them), and the ability to forward propagate an input through the layer (by relying on the forward function of the underlying neurons). It will also need to able to perform backwards propagation but we’ll talk about that in a future blog post.

Here is the code for layer (which is also a class) that fulfils the above requirements:

"""

A layer is a collection of Neurons

"""

import numpy as np

from .neuron import Neuron

from .activations import sigmoid

class Layer(object):

def __init__(self, size, num_inputs, type=Neuron, activation=sigmoid):

"""

:param size: The number of neurons in the layer

:param num_inputs: A matrix of shape (i, m).

- i is the number of neurons in the previous layer

- m is the number of training examples

:type: The type of neuron to use

"""

self.size = size

self.num_inputs = num_inputs

self.neuron_type = type

self.activation = activation

# Create all the neurons in this layer

self.neurons = []

for i in range(size):

self.neurons.append(Neuron(self.num_inputs, activation=self.activation))

def get_weights(self):

"""

We have a list of neuron objects with their associated weights.

For each item in the list, the shape will be a vector of length self.num_inputs

Therefore, we should concatenate these weights together, so that the layer weights will be (self.size, self.num_inputs)

:return: A matrix of shape (self.num_inputs, self.size)

"""

weights = np.zeros((self.size, self.num_inputs))

for idx, neuron in enumerate(self.neurons):

weights[idx, :] = np.squeeze(neuron.get_weights())

return weights

def set_weights(self, weights):

"""

Decomposes the weights matrix into a list of vectors to store into the Neuron weights.

:param weights: A matrix of shape (self.num_inputs, self.size)

:return:

"""

for idx, neuron in enumerate(self.neurons):

neuron.set_weights(weights[idx, :])

def forward(self, input):

"""

Performs a forward pass step, calculating the result of all neurons.

:param input: A matrix of shape (self.num_inputs, t) (from the previous layer or the overall input)

:return: A vector of length (self.size, t) (i.e. the result of the equation sigmoid(W.X + b)).

t is the number of training examples

"""

# In a more performant network, we should do a direct matrix multiplication for all Neurons

# But in our slower version we rely on the per neuron forward function to retrieve our forward propagation result

res = []

for idx, neuron in enumerate(self.neurons):

res.append(neuron.forward(input))

return np.vstack(res)

Above the layer, we have the network. This is the highest level of abstraction we have, and provides an easy interface to the user for specifying a network architecture as well as implementing what’s become a fairly standard set of functions for machine learning libraries nowadays - the fit and predict functions.

In this network class, we have so far just implemented the predict function as this is just a forward pass on the network, and it makes use of forward function of the layers within the network (which makes use of the forward function on the neurons in the layer). In this way, it will allow us to construct fully connected networks composed of an arbitrary number of layers with each layer having an arbitrary number of neurons.

"""

The top most class that we use to build a Neural Network

"""

import numpy as np

from .loss import *

from .layer import Layer

from .activations import sigmoid

from .neuron import Neuron

class Network(object):

def __init__(self, input_dim, hidden_layer_dim, optimiser=None, neuron_type=Neuron, activation=sigmoid):

self.input_dim = input_dim

self.hidden_layer_dim = hidden_layer_dim

self.optimiser = optimiser

self.neuron_type = neuron_type

self.activation = activation

self.layers = []

for idx, dim in enumerate(hidden_layer_dim):

# For the first hidden layer, the input dimension should be the overall input dimension

if idx == 0:

self.layers.append(Layer(dim, self.input_dim, type=self.neuron_type, activation=self.activation))

# For all other hidden layers, the layer size will use the previous layer size as input size, and the layer size specified in the config

else:

self.layers.append(Layer(dim, hidden_layer_dim[idx - 1], type=self.neuron_type, activation=self.activation))

def forward(self, input):

"""

The forward function which runs a forward pass on the entire network

:param input: A matrix of shape (input_dim, training_examples)

:return: A column vector representing the output of the final layer

"""

res = input

for layer in self.layers:

res = layer.forward(res)

return res

def backward(self, loss):

"""

The backward function that runs one backward propagation pass on the entire network

:param loss:

:return:

"""

raise NotImplementedError

def predict(self, input):

"""

Relies on the forward function to make inference

:param input: A column vector of length input_dim

:return: A column vector representing the output of the final layer

"""

return self.forward(input)

def fit(self, input, target):

"""

Trains the neural network given a set of data

:param input: A column vector of length input_dim

:param target: A target vector of length input_dim

:return:

"""

raise NotImplementedError

So, after this step we actually have what’s known as a Multilayer Perceptron (which is a fancy name to say a Neural Network that is fully connected between all layers).

If you are confused about what forward propagation means, it’s very simple. It simply means to pass an input through the network and get the output out at the other end (this is as opposed to backwards propagation, which we’ll tackle in a future blog post).

Finally, no library is complete without testing, so also in this update there are now unit tests available for the network so far.

These tests can be run with the pytest module:

pytest unit_tests.py

================================================= test session starts =================================================

platform darwin -- Python 3.6.2, pytest-3.5.1, py-1.5.3, pluggy-0.6.0

rootdir: /Users/qzhao/potatolemon/tests, inifile:

plugins: celery-4.1.0

collected 4 items

unit_tests.py .... [100%]

============================================== 4 passed in 0.11 seconds ===============================================

Ok, that’s all for now! Stay tuned for the next post, where we’ll start talking about what really gives neural networks the ability to learn.

All code can be found on the github project: https://github.com/qichaozhao/potatolemon

Peace out for now!

-qz