Text Understanding from Scratch

Machine Learning as a whole has now been officially outed by xkcd as nothing more than a slushy pile of linear algebra, where data goes in, math happens, and answers come out.

Despite this, I find it completely fascinating, and it is one of my own primary motivations to continue on this data science lark.

This field is, of course, bursting at the seams right now with interest, hype and hyperbole. Without completely derailing the whole point of this post, all I will say (for now) is that I believe large scale machine learning systems rank among some of the most complicated machines we have built, and as a technologist, that excites me to learn about them.

So, in this post, let’s not talk about the hype, but let’s talk about something that one of these systems can actually accomplish.

Text Understanding from Scratch

Casting about for projects to bolster my understanding of Keras (a deep learning framework for Python), I came across this paper: Text Understanding from Scratch

This just so happened to align with (surprise surprise), an interesting NLP classification problem at work which I thought it could be applied to.

Thoughts on the Paper

What really interested me about this approach to text classification is that it is completely domain agnostic. Based on my understanding, the domain is usually important when trying to perform NLP tasks using machine learning, as words mean different things given different contexts. In order to account for this, the popular approaches of recent times have been to create vector word embeddings (e.g. representing a word in a high dimensional vector space). This allows words that are different yet share similar semantics to be placed near each other in this vector space. It is then possible to use linear algebra to calculate things like “similarity” metrics between words.

However, the approach that this paper uses is a CNN that learns words from the character level upwards. Presumably, if given enough training data it will infer not only the relationships between characters, words and sentences, but also the implicit semantic relationships of any given domain that it is trained in to allow to do well at the classification task.

Although, in theory this all sounds very exciting, reading the paper does not reveal any real evidence that this is the case. We as humans require this to happen for us to be able to classify texts, but that’s not to say a machine would need to work in the same way. It may well just be a well stirred (but not shaken) slush pile of linear algebra.

The authors do show though that the way that they map inputs leads to a braille like representation of words (presumably this is why the CNN works well).

Regardless, the results that they report over their datasets were state of the art at the time, which validates the approach, but also what I think makes this method powerful is that it is quite general. One could in theory train this model on any text corpus from scratch and it would be able to do well at the classification task.

A criticism of this model I would have is that it seems light on the “Understanding” portion. With vector embeddings, we can get a sense of semantic similarities between words, and other approaches allow us to do things like “part of speech” tagging and other clever things that linguists know about that I don’t. So, while this method gives us very good accuracies on our classification task, it does not yield insight into the structure and nature of its “understanding”.

Maybe the paper should have been called “Text Classification from Scratch”, but I also feel like an insolent twerp suggesting that when it was clearly written by people much smarter than me.

Implementation

Enough pontificating, let’s talk nuts and bolts. Note you can see all the code on the github repo here: https://github.com/qichaozhao/pyCrepeK2

I created a class within crepe.py which would represent the model itself, and also the methods which we could interact with it (namely fit and a predict method a la sklearn’s convention). I also added a few internal helper functions to help pre-process the input in the right way for the model.

Let’s step through the functions sequentially, in the order that they would be called when using this class, and explain what they do.

def __init__(self, num_classes, model_loc='saved_models/crepe.hdf5', train_data_loc='data/train.csv', val_data_loc='data/test.csv', test_data_loc='data/test.csv'):

"""

Some global variables used by our model

"""

self.model_loc = model_loc

self.train_data_loc = train_data_loc

self.val_data_loc = val_data_loc

self.test_data_loc = test_data_loc

self.num_classes = num_classes

tr_df = pd.read_csv(self.train_data_loc)

va_df = pd.read_csv(self.val_data_loc)

te_df = pd.read_csv(self.test_data_loc)

self.num_train = len(tr_df)

self.num_val = len(va_df)

self.num_test = len(te_df)

# Define our Alphabet

self.alphabet = (list(string.ascii_lowercase) + list(string.digits) + list(string.punctuation))

self.alpha_map = {}

for idx, c in enumerate(self.alphabet):

self.alpha_map[c] = idx

# Initialise the model

self.model = self._get_model()

This is our initialisation function. The notable things here are that:

- We actually read in our datasets to determine the overall number of samples. If the training sets become very large, this method could be a bit memory prohibitive (we should probably use other methods like subprocessing a

wc -lbut this approach works just fine for the dataset we have). - We define an alphabet comprised of normal lower case characters, digits and punctuation, and associate them with an ordinal mapping. We’ll need this later to create our input frames.

After initialisation, the next thing we need to do is prepare the input data to feed into the model. This uses two functions: _data_gen which relies upon _get_char_seq.

def _data_gen(self, file_name, batch_size, mode='train'):

"""

A generator that yields a batch of samples.

Mode can be "train" or "pred".

If pred, only an X value is yielded.

"""

while True:

reader = pd.read_csv(file_name, chunksize=batch_size)

for data in reader:

data['X'] = data['X'].apply(lambda x: self._get_char_seq(str(x).lower()))

if mode == 'train':

yield (np.asarray(data['X'].tolist()), np_utils.to_categorical(np.asarray(data['y'].tolist()), num_classes=self.num_classes))

elif mode == 'pred':

yield np.asarray(data['X'].tolist())

else:

raise Exception('Invalid mode specified. Must be "train" or "pred".')

We will be making use of Keras’ fit_generator function when we come to do the training (and also predictions), so this function is actually a generator. All this means is that it allows us to limit the amount of training samples we have to hold in memory at any one point to a manageable subset, and makes it feasible for us to train this model on large datasets without maxing out our RAM.

If you’re not familiar with generators and how they work, I recommend this blog post/tutorial which will cover the basics: Click Me!

TL:DR though: a generator is like the pinata version of a function; every time you hit it some new goodies fall out until it runs out of goodies.

def _get_char_seq(self, desc):

"""

Converts a sequence of characters into a sequence of one hot encoded "frames"

"""

INPUT_LENGTH = 1014

seq = []

for char in list(reversed(desc))[0:INPUT_LENGTH]:

# we reverse the description then get the first 1014 chars (why 1014? Because that's what they did in the paper...)

# Get the index of character in the alphabet list

try:

fr = np.zeros(len(self.alphabet))

fr[self.alpha_map[char]] = 1

seq.append(fr)

except (ValueError, KeyError):

# character is not in index

seq.append(np.zeros(len(self.alphabet)))

# Now check the generated input and pad out to 1014 if too short

if INPUT_LENGTH - len(seq) > 0:

seq.extend([np.zeros(len(self.alphabet)) for i in range(0, INPUT_LENGTH - len(seq))])

return np.array(seq)

This function is actually our heavy lifting function in terms of processing the input. The approach described in the paper essentially processes each separate character and one-hot encodes using our alphabet dictionary.

What is one-hot encoding? It’s pretty simple. If we have an alphabet mapping where a=1, b=2, c=3. Then we can represent a as the array [1, 0, 0], b as [0, 1, 0] etc…

We do this encoding for the first 1014 characters in our input text and discard the rest. Why 1014? You’ll have to ask the authors!

With the input processed, we just need to define our model before we can train it.

def _get_model(self):

"""

Returns the model.

"""

k_init = RandomNormal(mean=0.0, stddev=0.05, seed=None)

model = Sequential()

# Layer 1

model.add(Convolution1D(input_shape=(1014, len(self.alphabet)), filters=256, kernel_size=7, padding='valid', activation='relu', kernel_initializer=k_init))

model.add(MaxPooling1D(pool_size=3, strides=3))

# Layer 2

model.add(Convolution1D(filters=256, kernel_size=7, padding='valid', activation='relu', kernel_initializer=k_init))

model.add(MaxPooling1D(pool_size=3, strides=3))

# Layer 3, 4, 5

model.add(Convolution1D(filters=256, kernel_size=3, padding='valid', activation='relu', kernel_initializer=k_init))

model.add(Convolution1D(filters=256, kernel_size=3, padding='valid', activation='relu', kernel_initializer=k_init))

model.add(Convolution1D(filters=256, kernel_size=3, padding='valid', activation='relu', kernel_initializer=k_init))

# Layer 6

model.add(Convolution1D(filters=256, kernel_size=3, padding='valid', activation='relu', kernel_initializer=k_init))

model.add(MaxPooling1D(pool_size=3, strides=3))

# Layer 7

model.add(Flatten())

model.add(Dense(1024, activation='relu', kernel_initializer=k_init))

model.add(Dropout(0.5))

# Layer 8

model.add(Dense(1024, activation='relu', kernel_initializer=k_init))

model.add(Dropout(0.5))

# Layer 9

model.add(Dense(self.num_classes, activation='softmax'))

model.compile(loss='categorical_crossentropy', optimizer='adam', metrics=['accuracy'])

return model

For me, this is the beauty of Keras. A state of the art neural network, represented in just 30 lines of code.

The only difference in this implementation vs the version outlined in the paper is that I have chosen to use the ADAM optimisation scheme versus vanilla SGD. As far as I understand it, ADAM is SGD with bells and whistles, and purportedly performs better.

Now, we can go to our training function:

def fit(self, batch_size=100, epochs=5):

"""

The fit function.

"""

# set up our data generators

train_data = self._data_gen(self.train_data_loc, batch_size)

val_data = self._data_gen(self.val_data_loc, batch_size)

print(self.model.summary())

self.model.fit_generator(generator=train_data, steps_per_epoch=self.num_train / batch_size,

validation_data=val_data, validation_steps=self.num_val / batch_size,

epochs=epochs, callbacks=self._get_callbacks(), verbose=1)

This relies on the _data_gen function we walked through earlier to set up the inputs, and then uses Keras’ fit_generator function to train our weights. Simple as that. A slight twist I have added here is the use of some callbacks, which I have defined in the _get_callbacks function.

def _get_callbacks(self):

"""

A helper function which defines our callbacks

"""

# Define our model callbacks and save path, checkpoint

reduce_lr = ReduceLROnPlateau(monitor='val_loss', factor=0.2, patience=2, verbose=1, min_lr=0.001, mode='min')

earlyStop = EarlyStopping(monitor='val_loss', min_delta=0, patience=3, verbose=1, mode='min')

checkpoint = ModelCheckpoint(self.model_loc, monitor='val_acc', verbose=1, save_best_only=True, mode='max')

return [checkpoint, reduce_lr, earlyStop]

These callbacks are run after the end of every epoch, and just allows us at the end of every epoch to make a few checks:

- Save the model weights if we score a new “best” accuracy.

- Reduce the learning rate if we see our results plateau for 2 epochs straight, to see if that allows us to improve things.

- Stop the training process early if we see our results plateau for 3 epochs straight, to avoid wasting training time.

We’re nearly there!

Once our neural network is trained, we should evaluate its performance on a hold-out or test set. We can do this with an evaluation function:

def evaluate(self, batch_size=100):

"""

Prints the evaluation score, using the current weights and the specified test set.

"""

test_data = self._data_gen(self.test_data_loc, batch_size)

score = model.evaluate_generator(generator=test_data, steps=self.num_val / batch_size)

print 'Test Loss: ' + score[0]

print 'Test Accuracy: ' + score[1]

And finally, we have our prediction function, which is kind of the whole point of training up a neural network. We can use this to return an array of probabilities for each category per input.

Note again we are relying on the _datagen function, this allows us to make predictions for a large number of inputs all at once!

def predict(self, batch_size=100, pred_data_loc=None, model_loc=None):

"""

Predicts using the current weights (or can specify a set of weights to be loaded).

"""

# If we don't have an input, then we just use the test data previously specified

# Otherwise, predict using the new input

if pred_data_loc is None:

pred_data = self.test_data_loc

else:

pred_data = pred_data_loc

pr_df = pd.read_csv(pred_data)

num_pred = len(pr_df)

pred_data = self._data_gen(pred_data, batch_size, mode='pred')

# Check if we have a weight file being passed, if so, load that, otherwise don't.

if model_loc:

self.model.load_weights(model_loc)

return self.model.predict_generator(generator=pred_data, steps=num_pred / batch_size)

Putting everything together in a class, we essentially now have a self-contained text classification hammer that can be deployed with extreme prejudice on our naily classification problem of choice. Exciting!

Results

Let’s assume our naily classification problem of choice just so happens to be classifying the topics of the AG News dataset that we find in the github repo (convenient eh?).

I trained the model on an AWS GPU instance through a python notebook (also found in the github repo). I won’t talk through the steps explicitly as I feel it is quite well documented in the notebook.

The overall result I was able to get after 8 or so epochs of training were as follows:

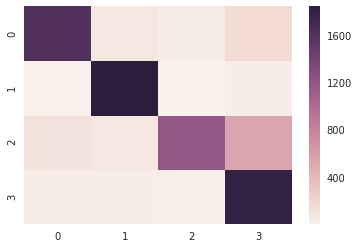

Confusion Matrix

Classification Report

precision recall f1-score support

0 0.91 0.86 0.88 1900

1 0.91 0.97 0.94 1900

2 0.95 0.62 0.75 1900

3 0.71 0.95 0.81 1900

avg / total 0.87 0.85 0.85 7600

These results are very much in line with the results reported in the paper (though there the metric they used was accuracy rather than F1-score), but, regardless, very good!

So, there we have it.

In this blog post we stepped through an end to end implementation of a deep learning model in Keras.

This deep learning model can be used for text classification tasks and enjoys a state of the art accuracy (as of when the paper was published anyway).

We used our implementation to replicate the results obtained in the paper for the AG News dataset, and were able to successfully do so.

Hooray!

All code can be found in the repository. https://github.com/qichaozhao/pyCrepeK2

-qz